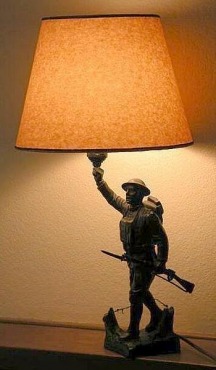

Spirit of the American Doughboy "ART Lamp"

"THE CASE OF THE MISSING DOUGHBOY"

Grandma's Doughboy Lamp

All I wanted was some information about the curious little lamp given to me by my mother. Before that, it had belonged to her mother, who bought it in a Muskegon Heights, MI, furniture store in 1923. It was bought to honor Grandma's brother-in-law, our "Uncle Barney" Quater, who, although not a Doughboy, had joined and served in the Canadian Army in France during the "Great War". The lamp had been in the family ever since. We knew it represented a U.S. WWI soldier, who was called a "Doughboy" back then, so we always referred to it as "our Doughboy lamp"; but other than that, we had no idea of its history, or anything else about it, including who E.M. Viquesney, the sculptor, was. And until the advent of the World Wide Web, neither did most anybody else. Antique shops and dealers I visited had never heard of Viquesney or his lamp, and I knew of no other owners. Other than the sculptor's name and location (Americus, Georgia) on the back of the base, there was just the title, "Spirit of the American Doughboy" on the front (the original paper label on the bottom with more information had long disappeared).

I tried having the lamp researched in 1991; it was reported to me that there were no references to it, or the sculptor, in any antique guides concerning lamps or metal art objects. The report went on to state that my lamp was probably a "limited production item", which turned out to be 180 degrees off the mark, as you'll see below. Finally, when the World Wide Web became available, I began to do my own research.

However, when I first found references to "E. M. Viquesney" or "Spirit of the American Doughboy" on the Web, all that showed up were sites concerned with the large Viquesney Doughboy statues that still stand in various locations throughout the nation. But at least I now knew the original inspiration for the lamp. I e-mailed my mother with the news: "Mom", I said, "it looks like our Doughboy lamp has some big brothers..."

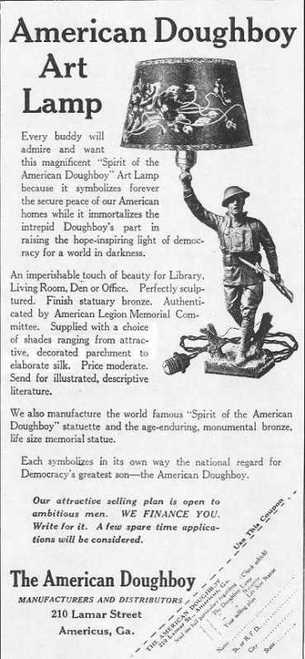

It turned out that American Legion Weekly had run ads throughout the 1920s for the "American Doughboy Art Lamp" as it was first called. It also turned out that a newspaper editor in Spencer, Indiana, T. Perry Wesley, had researched Viquesney and his works for 50 years. And I found out my "limited production item" had surpassed 25,000 units in various versions by the middle of 1927. But if they were once so common, where were they now?

Finally, in 2000, my wife, Jo Ann, a librarian, found a posting on the Internet titled "The Case of the Missing Doughboy", whose author, David Homsher, had also been searching for the same mysterious little lamp. Through him, I was at last put in touch with another lamp owner, Mark Evans, of Clearfield, Pennsylvania. We excitedly traded notes and stories; until then, I had the delusion that my Doughboy lamp might be the only one in existence. But it turned out there were other owners out there; in Chicago, Illinois, Charles Kroon had posted a message on Google way back in 1997, which had remained unanswered until 2002, when I found it, asking for help in identifying two old lamps he had. One of them bore a description I instantly recognized as a Viquesney Doughboy miniature, but converted into a night light with a miniature bulb socket mounted on top of the right hand.

Messages I posted to various Internet bulletin boards turned up a few more owners. But often I would forget to check back for replies. Finally the idea came to me to put up a website; there might be still others looking for information on that "little WWI soldier statue" found at an estate sale or discovered in an old trunk. It is thus my hope that this site will bring even more Doughboy lamps and statuettes "out of the attic". (Ed. note: Since publication of my original website in 2002, literally hundreds of Viquesney miniatures have appeared on eBay and other online auction sites.)

Finally in 2002 I was put in contact with Earl Goldsmith of The Woodlands, Texas, who had picked up the research of T. Perry Wesley. Earl kindly supplied most of the descriptions and locations of the life-size Viquesney Doughboy monuments found throughout the country. Earl's data, combined with my own, has resulted in the current website (not to mention multiplying the number of site visitors by at least five times).

I tried having the lamp researched in 1991; it was reported to me that there were no references to it, or the sculptor, in any antique guides concerning lamps or metal art objects. The report went on to state that my lamp was probably a "limited production item", which turned out to be 180 degrees off the mark, as you'll see below. Finally, when the World Wide Web became available, I began to do my own research.

However, when I first found references to "E. M. Viquesney" or "Spirit of the American Doughboy" on the Web, all that showed up were sites concerned with the large Viquesney Doughboy statues that still stand in various locations throughout the nation. But at least I now knew the original inspiration for the lamp. I e-mailed my mother with the news: "Mom", I said, "it looks like our Doughboy lamp has some big brothers..."

It turned out that American Legion Weekly had run ads throughout the 1920s for the "American Doughboy Art Lamp" as it was first called. It also turned out that a newspaper editor in Spencer, Indiana, T. Perry Wesley, had researched Viquesney and his works for 50 years. And I found out my "limited production item" had surpassed 25,000 units in various versions by the middle of 1927. But if they were once so common, where were they now?

Finally, in 2000, my wife, Jo Ann, a librarian, found a posting on the Internet titled "The Case of the Missing Doughboy", whose author, David Homsher, had also been searching for the same mysterious little lamp. Through him, I was at last put in touch with another lamp owner, Mark Evans, of Clearfield, Pennsylvania. We excitedly traded notes and stories; until then, I had the delusion that my Doughboy lamp might be the only one in existence. But it turned out there were other owners out there; in Chicago, Illinois, Charles Kroon had posted a message on Google way back in 1997, which had remained unanswered until 2002, when I found it, asking for help in identifying two old lamps he had. One of them bore a description I instantly recognized as a Viquesney Doughboy miniature, but converted into a night light with a miniature bulb socket mounted on top of the right hand.

Messages I posted to various Internet bulletin boards turned up a few more owners. But often I would forget to check back for replies. Finally the idea came to me to put up a website; there might be still others looking for information on that "little WWI soldier statue" found at an estate sale or discovered in an old trunk. It is thus my hope that this site will bring even more Doughboy lamps and statuettes "out of the attic". (Ed. note: Since publication of my original website in 2002, literally hundreds of Viquesney miniatures have appeared on eBay and other online auction sites.)

Finally in 2002 I was put in contact with Earl Goldsmith of The Woodlands, Texas, who had picked up the research of T. Perry Wesley. Earl kindly supplied most of the descriptions and locations of the life-size Viquesney Doughboy monuments found throughout the country. Earl's data, combined with my own, has resulted in the current website (not to mention multiplying the number of site visitors by at least five times).

LAMP DESCRIPTION

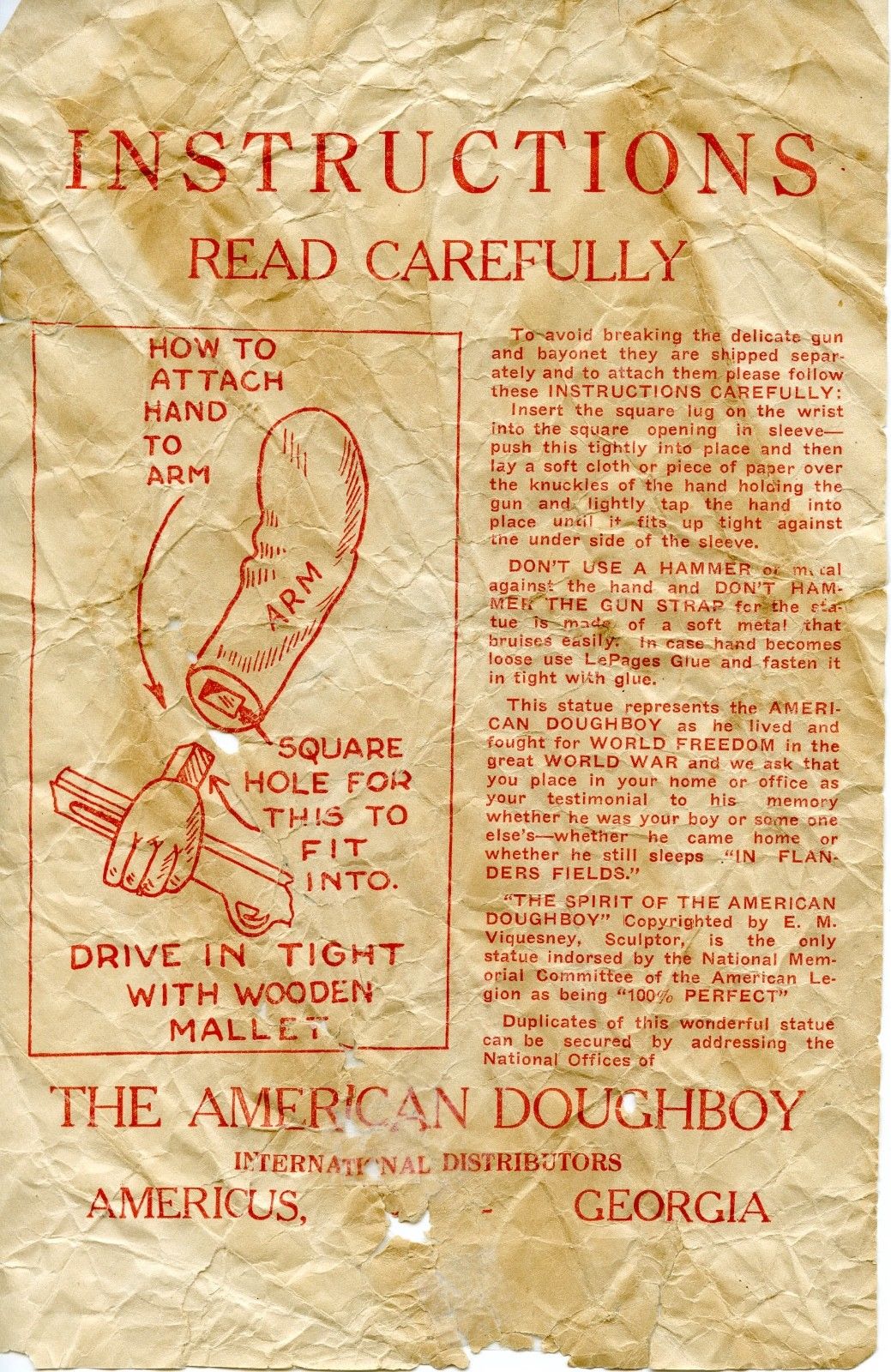

Grandma's Doughboy lamp originally came with the paper red poppy motif shade, the sticker on the bottom, and the instruction sheet pictured below, but all eventually disappeared over the years.

The instruction sheet describes a serious design flaw in the piece: The left hand and rifle were cast as a separate unit with a lug projecting off the wrist, which had to be glued into a hole in the left sleeve. Since there was no "Super-Glue" back in those days, the rifle often would fall out and get lost or broken. Grandma solved this problem by having the left hand and rifle permanently soldered onto our lamp, but it made the left sleeve cuff look a little rough.

Although the Doughboy lamp was available at retail outlets (my grandmother, as noted, bought hers at a furniture store), Viquesney's main sales venue was mail order. After prospective customers had answered ads like those above, they were sent a brochure that more fully described the product.

Buddy and Judy Parker of Hampton, Virginia discovered a lamp owned by Buddy's grandfather, who saved copies of the sales literature after he ordered his lamp.

The Parkers' complete brochure can be seen at our Viquesney Archive website.

Buddy and Judy Parker of Hampton, Virginia discovered a lamp owned by Buddy's grandfather, who saved copies of the sales literature after he ordered his lamp.

The Parkers' complete brochure can be seen at our Viquesney Archive website.

|

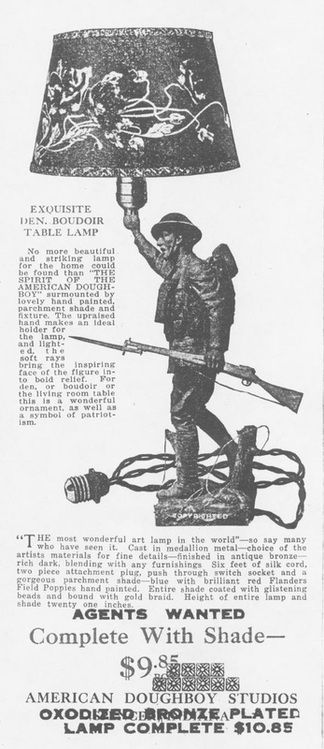

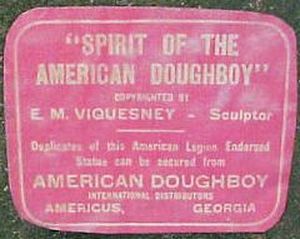

The figurine is 11.5 inches tall to the top of the right hand, and stands on a 3.5-inch square base. The socket adds another 2.5 inches to the height. The front of the base bears the inscription "Spirit of the American Doughboy", and on the back, "Copyrighted by E.M. Viquesney, Sculptor, Americus, Georgia" (or "Spencer, Indiana"; sometimes the year 1920 is included). Like its namesake, the life-size WWI memorial statue, the figurine depicts an American Infantryman advancing with a rifle and grenade. The clip-on lampshade, attached to the light bulb, was decorated with what was described in the old ads as a "red Flanders poppy design" on a "blue parchment" background. There were other solid colors on silk shades available as well in rose, blue, or gold.

The earliest lamps, like the one shown at right, are marked Americus, Georgia on the back, and began appearing almost immediately after the original statuette version. They were described as having a "statuary bronze" finish, which fooled many customers into believing they had purchased a bronze piece, when it was just a cast lead statuette with a coating of an almost-black paint finish called dark chocolate, to simulate the look of an old bronze statue. The soft lead broke easily, and may be one of the contributing factors as to why complete lamps are now so rare. Especially vulnerable to damage was the thin, unreinforced bayonet which easily broke off. The Americus lamps were produced from circa 1922 - 1925 and sold for $9.85 postpaid, and had what was described as a "statuary bronze" finish, which was really just a dark brown, almost black paint coating. Models from 1926 and later, bearing a Spencer, Indiana logo, also added a "higher-end" $10.85 version with a real bronze-plated finish, and another $9.85 finish called "bronze spray", which was simply bronze-colored paint. With its heavy socket and lampshade assembly, the lamp was more off-centered than the more stable Doughboy statuettes, and tipped over easily. This was because the lamp was simply the statuette version to which electrical hardware was attached. It was never designed from scratch to be a well-balanced a lamp. Still, the "American Doughboy Art Lamp" was once common and quite popular during the period just after WWI. It was once advertised as "the nation's most beautiful patriotic lamp", but today there are only a few of these pieces still in working order. But although rare, collectors seem to favor the more common statuette version, so the monetary value is no greater for the lamps, and often much less. |

Above and left: Homemade lamps made from the statuette version. The factory-issue lamps had the electric wire running up inside the figurine.

|