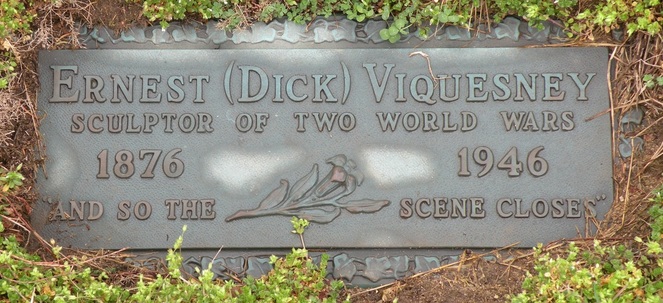

"And So the Scene Closes..."

Actual age at death was 70.

It was during the Summer of 1918, that E. M. Viquesney first conceived, with a few sketches, the idea of an enduring monument to all those who had served and died in the still ongoing World War. A year later, the first working clay model had been completed, and in 1920, Viquesney copyrighted what was to become the most famous war memorial statue in U.S. history, "The Spirit of the American Doughboy".

Viquesney didn't want his statue to portray the glamour and heroics of the American Doughboy in battle, but rather he wanted to show what the average hometown soldier had to endure in war, burdened under his heavy backpack, armed with a viciously bayoneted rifle, and carrying a gas mask pouch. Viquesney hoped people would look at his statue and turn away from war.

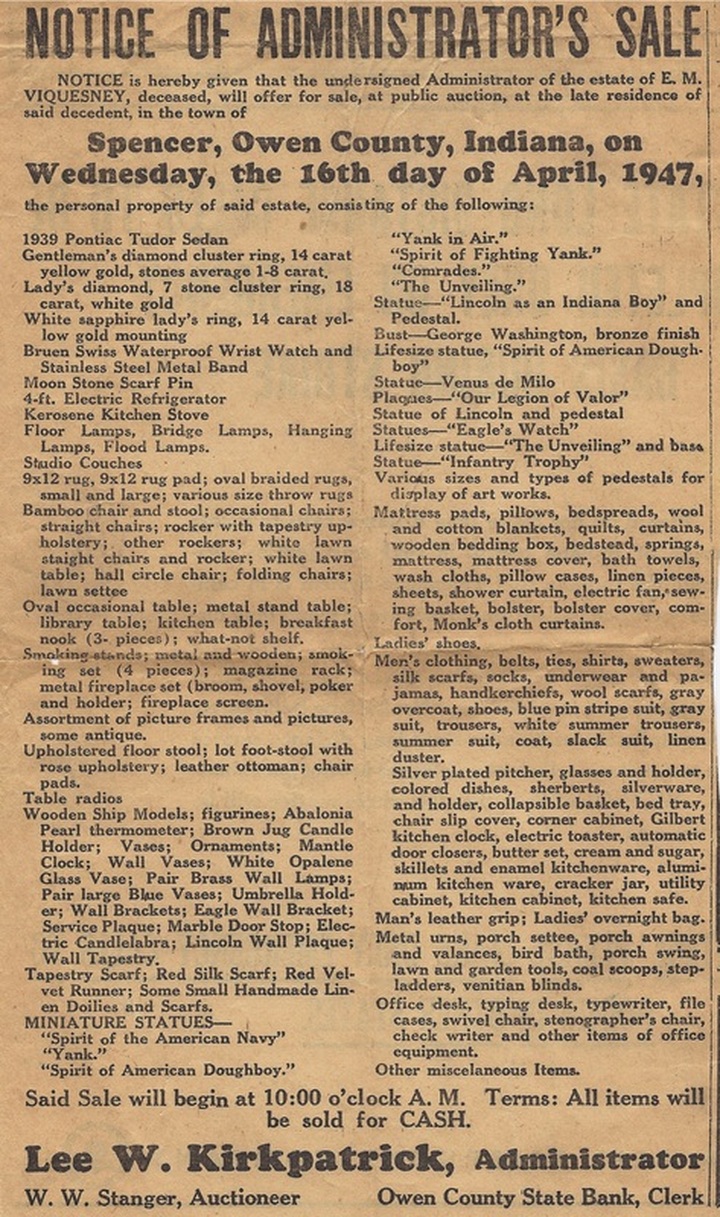

But in 1941 war came again, and the nation became focused on America's new soldier, the G.I., causing interest in Viquesney's "Spirit of the American Doughboy" to dwindle. However, throughout WWII Viquesney continued as a sculptor, making many G.I.-themed pieces. But with his death in 1946, most of the miniatures he produced throughout his long career, including the Doughboy lamp and statuette, seemed to rapidly and unaccountably disappear.

It is somewhat ironic that Viquesney is today almost forgotten. Many artists go unrecognized during their lifetimes, only to become famous after their deaths. Viquesney was one of that select group who did become famous and recognized during his lifetime. But because he "mass-produced" his Doughboy and often resorted to deceptive advertising practices, later generations, if they remember him at all, often refer to him at best as a canny marketer, or at worst, a crass entrepreneur. There are even today some shortsighted officials in many cities and towns that possess Viquesney Doughboys who see no need for preserving what has now become a national treasure.

Viquesney was a self-promoter. He had a monumental (pardon the pun) ego, referring to himself in his own sales literature as "a famous sculptor", and described in flowery, patriotic prose, the beauty, perfection, style, and grandeur of his own works. Further, these descriptions were usually written in the third-person, to make it sound like someone else was heaping praise upon him. And of course, he relied heavily on glowing letters and "testimonials" from customers.

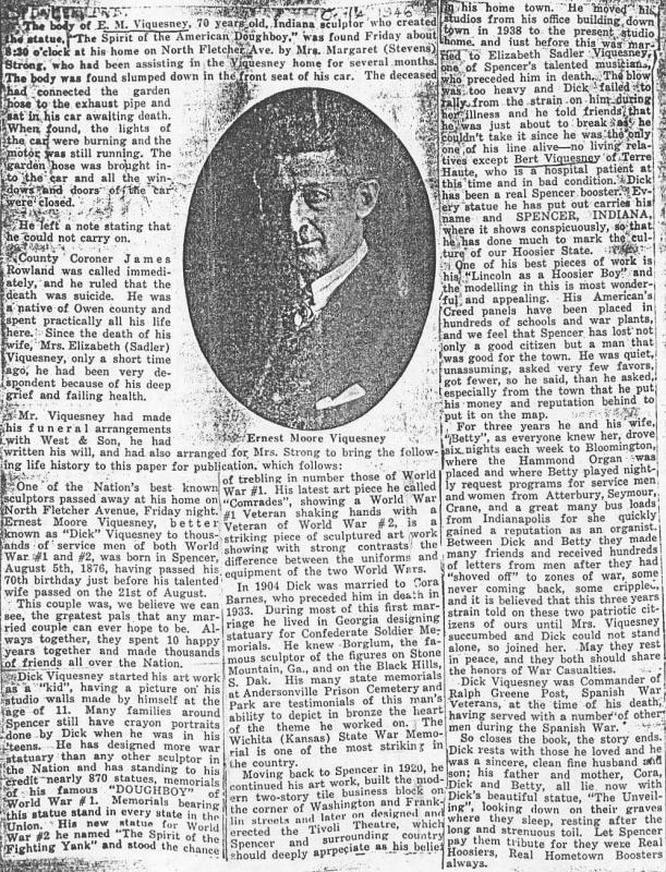

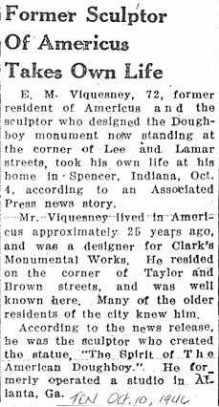

Two months after the death of his second wife, Betty, Viquesney committed suicide October 5, 1946. He wrote his own long-winded, self-aggrandizing obituary, which took up the better part of three newspaper columns. In it, there is no mention of the sale of his Doughboy company to Walter Rylander in 1922. Instead, Viquesney claimed he moved back to Spencer, Indiana, in 1920, which is not exactly true: Although he spent a few weeks in Spencer at the turn of the year in 1920, perhaps in anticipation of his return, he was still living in Americus, Georgia, until the end of January, 1922, leaving for Spencer permanently shortly after the sale occurred. Viquesney also claimed that every statue he ever made bore the name of his hometown of Spencer, but in fact, Viquesney's first Doughboy statue and many others bear the name of Americus, Georgia, and were in fact the ones responsible for rocketing him to fame.

In his obituary below, Viquesney claimed to have produced nearly 870 "Spirit of the American Doughboy" memorials. If true, that leaves quite a few unaccounted for. Most researchers dismiss Viquesney's final claims as the rantings of a mind deranged by grief over the death of his wife, but what if, by outside chance, he was right...?

"Don't ever bother with art", Alfred Paul Viquesney once said to his son. "If you do, you'll die a poor man." It's lucky young "Dick" didn't follow his father's advice, for although he didn't die a wealthy man, Ernest Moore Viquesney indeed left us a rich legacy in WWI statuary. So look closely in your city parks, town squares, courthouse lawns, and military cemeteries for "The Spirit of the American Doughboy"; the ones that remain still stand as silent sentinels honoring not only those who served and died in "The War to End All Wars", but also their creator, Ernest Moore Viquesney.

Viquesney didn't want his statue to portray the glamour and heroics of the American Doughboy in battle, but rather he wanted to show what the average hometown soldier had to endure in war, burdened under his heavy backpack, armed with a viciously bayoneted rifle, and carrying a gas mask pouch. Viquesney hoped people would look at his statue and turn away from war.

But in 1941 war came again, and the nation became focused on America's new soldier, the G.I., causing interest in Viquesney's "Spirit of the American Doughboy" to dwindle. However, throughout WWII Viquesney continued as a sculptor, making many G.I.-themed pieces. But with his death in 1946, most of the miniatures he produced throughout his long career, including the Doughboy lamp and statuette, seemed to rapidly and unaccountably disappear.

It is somewhat ironic that Viquesney is today almost forgotten. Many artists go unrecognized during their lifetimes, only to become famous after their deaths. Viquesney was one of that select group who did become famous and recognized during his lifetime. But because he "mass-produced" his Doughboy and often resorted to deceptive advertising practices, later generations, if they remember him at all, often refer to him at best as a canny marketer, or at worst, a crass entrepreneur. There are even today some shortsighted officials in many cities and towns that possess Viquesney Doughboys who see no need for preserving what has now become a national treasure.

Viquesney was a self-promoter. He had a monumental (pardon the pun) ego, referring to himself in his own sales literature as "a famous sculptor", and described in flowery, patriotic prose, the beauty, perfection, style, and grandeur of his own works. Further, these descriptions were usually written in the third-person, to make it sound like someone else was heaping praise upon him. And of course, he relied heavily on glowing letters and "testimonials" from customers.

Two months after the death of his second wife, Betty, Viquesney committed suicide October 5, 1946. He wrote his own long-winded, self-aggrandizing obituary, which took up the better part of three newspaper columns. In it, there is no mention of the sale of his Doughboy company to Walter Rylander in 1922. Instead, Viquesney claimed he moved back to Spencer, Indiana, in 1920, which is not exactly true: Although he spent a few weeks in Spencer at the turn of the year in 1920, perhaps in anticipation of his return, he was still living in Americus, Georgia, until the end of January, 1922, leaving for Spencer permanently shortly after the sale occurred. Viquesney also claimed that every statue he ever made bore the name of his hometown of Spencer, but in fact, Viquesney's first Doughboy statue and many others bear the name of Americus, Georgia, and were in fact the ones responsible for rocketing him to fame.

In his obituary below, Viquesney claimed to have produced nearly 870 "Spirit of the American Doughboy" memorials. If true, that leaves quite a few unaccounted for. Most researchers dismiss Viquesney's final claims as the rantings of a mind deranged by grief over the death of his wife, but what if, by outside chance, he was right...?

"Don't ever bother with art", Alfred Paul Viquesney once said to his son. "If you do, you'll die a poor man." It's lucky young "Dick" didn't follow his father's advice, for although he didn't die a wealthy man, Ernest Moore Viquesney indeed left us a rich legacy in WWI statuary. So look closely in your city parks, town squares, courthouse lawns, and military cemeteries for "The Spirit of the American Doughboy"; the ones that remain still stand as silent sentinels honoring not only those who served and died in "The War to End All Wars", but also their creator, Ernest Moore Viquesney.

Viquesney plowed most of his profits back into his business. At the time of his death, his estate was valued at only about $46,000.

Links:

waymarking.com

waymarking.com