See my Facebook Group for a more interactive experience.

T. PERRY WESLEY

1905 - 2001

The original E. M. Viquesney researcher

------

A Remembrance

by

Earl D. Goldsmith

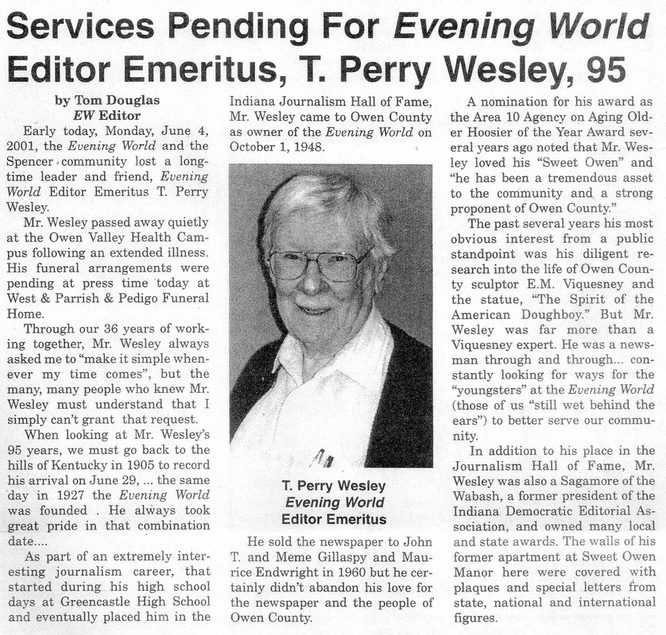

Until his death in 2001, the most widely recognized Viquesney Doughboy expert was T. Perry Wesley of Spencer, Indiana.

Mr. Wesley never knew Viquesney, since he didn’t arrive in Spencer until he bought the Spencer Evening World in 1948, two years after Viquesney’s death. But as a hobby, starting in the 1950s, he began collecting information about Viquesney and his Doughboy and other sculptures, continuing his quest right up until the time of his death on June 4, 2001. Much of what is known today about E. M. Viquesney and his creations comes from information Mr. Wesley gathered and published in a 1991 report. Even in his advanced age (he was born in 1905 in Casey County, Kentucky), people continued to call him for information until within a month or two before he died. His last weekly column as Editor-emeritus of the Evening World was published after he died. He was a remarkable man.

Mr. Wesley did an outstanding job of locating Viquesney’s Doughboys, but because of the lack of complete records, no list of locations will ever be known to include every Viquesney “Spirit'". Further, every list I have seen compiled by others erroneously includes other sculptures or locations where no Doughboy is known to have been placed.

This is at least partially due to the fact that, in the Summer of 1990, Mr. Wesley sent a letter and photo of Spencer's statue to the editor of Home and Away magazine asking people to advise him about locations of Viquesney's Doughboy. His letter was published, and while it resulted in locating many Viquesney Doughboys, he also received many erroneous responses, despite the clear photo he sent with the letter. Some respondents identified other similar-looking sculptures as Viquesney's Doughboy. Many of those were WWI monuments by John Paulding, but some were Civil War, Spanish American War, or other non-Doughboy figures. Some were sculptures people had seen somewhere in their travels and reported to Mr. Wesley, but often misremembering what they saw, or the names of the towns where they saw it. For a good example of this faulty recall, see this web page.

Mr. Wesley set out to verify those of which he had been advised, but because of his age and limited resources, could only do a valiant, rather than complete, job. He sent information about several unverified locations, including several John Paulding Doughboys, with descriptions indicating they were Viquesney Doughboys, in a response to a Smithsonian project. The result is that confusion has increased because of their inclusion in the Smithsonian’s Inventory of American Sculpture (IAS). Smithsonian representatives are aware of this and have indicated their willingness to make any corrections for which documentation is received, but once a report by Mr. Wesley was turned in, proving to the Smithsonian that a statue was incorrectly identified or never existed has been frustrating, such was his reputation as a Viquesney researcher.

After I had seen a few Doughboys and knew the locations of a few more, I wanted to see if I could find out where the others were, how many there were, and other information about them; I didn’t imagine there would be anywhere near as many as there are. In going through the Henryetta, Oklahoma library files during a visit there, I encountered a copy of T. P. Wesley’s letter to Home and Away, but the copy I saw didn’t indicate the name of the magazine or its date, so I couldn’t contact them. It did, however, have Mr. Wesley’s home address at the time. So I went through information operators. When I told the information operator his name, her response gave me the distinct impression that she knew of him. Fortunately, he still lived at that address and I managed to reach him on the phone. His hearing was very bad and after an attempt to introduce myself and the reason for the call, he told me that he was 92 and I’d have to speak up and speak slowly and clearly, so I started over. At the word, “Doughboy,” he took over. The dear man talked for about 45 minutes without pausing. I heard more about Doughboys than I thought possibly existed. I learned the rough number that exists. I heard of a stone one in my wife’s hometown that she hadn’t recognized as being one because it is stone. He even told me a humorous old story about the one in Henryetta and the name of a clothier he knew there when he was selling men's clothes in Oklahoma City in the 1920s. I could hardly get into the conversation – but he probably wouldn’t have heard me anyway. Before the call ended, we exchanged addresses and phone numbers and agreed that we would be in contact.

Within a few days, I had a thick package of information he’d mailed me about Viquesney and the Doughboy, and about Spencer and Owen County, Indiana – he was very proud of both. As we continued to have contact, he’d have Mary Lee Brinson, who lived a few doors from him in the same senior citizen apartments, listen to me about things he didn’t hear clearly and repeat my comments or questions to him. Then he would get on the phone with his deep voice and my end of the conversation was over again – but it was always enjoyable. Mary Lee also helped in his mailings to me. Over time, I learned how dependent he was on Mary Lee’s help and how strong their feelings for one another were, and she became an integral part of the relationship.

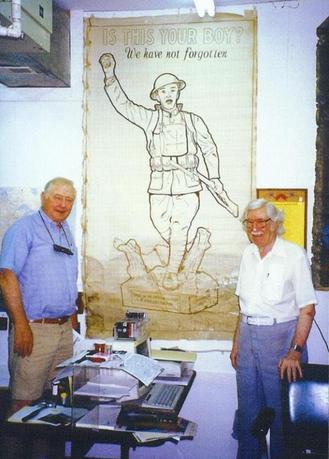

So Mr. Wesley was my very good friend, as was Mary Lee. We communicated often, even visited Viquesney’s grave together and dined at his favorite eating place, Spencer’s Canyon Inn at McCormick Creek State Park. I visited the office that the Evening World still maintained for him forty years after he had sold the paper, and I got to meet all the people there that he loved so much. I still communicate frequently with Mary Lee.

Since Mr. Wesley’s vision and writing had started to fail, he made me some audio tapes to record his recollections of Viquesney and Doughboy facts, and other things about Spencer and Owen County. I’d send him empty tapes to record more.

In early 2000, I took my two sisters on a 11 day driving trip to renew childhood memories, and we spent some of that time in Spencer so we could all share time with Mr. Wesley and Mary Lee. We also managed to see six Doughboys on the trip - plus one John Paulding Doughboy and three dead ends with no doughboys. Actually, we had a fourth dead end when we couldn’t get inside the Evansville American Legion Post to see their Doughboy.

Mr. Wesley moved to a nursing home – Owen Valley Health Campus – in September 2000 and spent his last nine months there. I was able to talk with him just a few times after the move, but Mary Lee and I were in very frequent contact and she would tell him of my calls. During his last months, I helped him by responding to two reporters writing articles about war monuments and his 50-year search for Doughboys, and to Don Conrad, who was compiling a travel guide to WWI monuments. Tom Douglas, editor of the Spencer Evening World, (now retired) also helped him.

Mr. Wesley died at Owen Valley early on June 4, 2001, just 25 days before his 96th birthday and I made calls that day to try to tell some of his “Doughboy Searchers” he had told me about. He is especially missed by his daughter, Betty Jo Blunk, by his dear caregiver and special love of his last few years, Mary Lee Brinson, by Tom Douglas and the entire staff of the Evening World, by many Spencer residents (he was called “Our Mr. Wesley” in Spencer), by his “Doughboy Searchers,” of which there have been quite a few – and by me. So highly regarded was the man, that in his memory there is now a T. Perry Wesley Community Leader Award presented annually to deserving Owen County residents by the local Chamber of Commerce.

One of the reporters I helped for Mr. Wesley was Reuters reporter Phil Barbara who was writing an article about Mr. Wesley’s 50 year quest to locate Viquesney Doughboys. Robert Widener of VFW Magazine contacted me about the same time about an article they were publishing in their Memorial Day issue, and it was as a result of contacts with one of the editors of the magazine that Les Kopel first learned of me. Mr. Barbara’s article was originally planned to be a Memorial Day article, but he became concerned that Mr. Wesley might not live that long, so it was published May 17, 2001. Mr. Barbara had been able to talk with Mr. Wesley on a limited basis and quoted him to me as saying that when he was gone, a man in Texas named Earl Goldsmith would pick up his search. Mr. Barbara was going to Europe later in May, I think to do an article about D-Day. He was concerned that Mr. Wesley would die before he returned, so he wrote an obituary and gave it to the person at Reuters in Washington D. C. who was in charge of releasing things at the correct time (City Desk, City Editor, or something like that). He then called me and gave me the phone number to call to reach that person as soon as I learned Mr. Wesley had died. I called the number on June 4 and they released the obituary. Unfortunately, it wasn’t picked up by a lot of newspapers because of the lack of widespread interest. I found it on the Internet at the time, but for the life of me, can’t locate a copy in my files.

Back to Mr. Wesley’s statement that a man in Texas would pick up his search: I didn’t have any plans along those lines, even though I was interested in seeing a few. By the time Mr. Wesley died, I had probably seen about fifteen. I had the Smithsonian list and was already aware of some corrections that should be made to it. I had an immense appreciation for Mr. Wesley and enjoyed knowing about Doughboys, but I wasn’t bent on trying to pinpoint all of them or come up with an authoritatively correct list of locations.

Within days of Mr. Wesley’s death, that changed. I just decided that I would start spending time trying to run down all the information I could about them. Since then, I’ve had phone conversations and written communications with people all across the country. I hacked along and made quite a bit of progress by myself for a while, and then Les Kopel came along to give me a big and continuous boost.

Mr. Wesley’s records contained about 35 erroneous Viquesney Doughboys, but did not reflect about 35-40 other genuine ones that have since been located. In the end, he had settled on a number that is very close to the number that is actually known. Les and I have combined efforts to compile a list that contains only Viquesney's World War I Doughboys or copies by other artists but credited to him, or not credited but using his original molds.

As time passes, we will find more.

Mr. Wesley never knew Viquesney, since he didn’t arrive in Spencer until he bought the Spencer Evening World in 1948, two years after Viquesney’s death. But as a hobby, starting in the 1950s, he began collecting information about Viquesney and his Doughboy and other sculptures, continuing his quest right up until the time of his death on June 4, 2001. Much of what is known today about E. M. Viquesney and his creations comes from information Mr. Wesley gathered and published in a 1991 report. Even in his advanced age (he was born in 1905 in Casey County, Kentucky), people continued to call him for information until within a month or two before he died. His last weekly column as Editor-emeritus of the Evening World was published after he died. He was a remarkable man.

Mr. Wesley did an outstanding job of locating Viquesney’s Doughboys, but because of the lack of complete records, no list of locations will ever be known to include every Viquesney “Spirit'". Further, every list I have seen compiled by others erroneously includes other sculptures or locations where no Doughboy is known to have been placed.

This is at least partially due to the fact that, in the Summer of 1990, Mr. Wesley sent a letter and photo of Spencer's statue to the editor of Home and Away magazine asking people to advise him about locations of Viquesney's Doughboy. His letter was published, and while it resulted in locating many Viquesney Doughboys, he also received many erroneous responses, despite the clear photo he sent with the letter. Some respondents identified other similar-looking sculptures as Viquesney's Doughboy. Many of those were WWI monuments by John Paulding, but some were Civil War, Spanish American War, or other non-Doughboy figures. Some were sculptures people had seen somewhere in their travels and reported to Mr. Wesley, but often misremembering what they saw, or the names of the towns where they saw it. For a good example of this faulty recall, see this web page.

Mr. Wesley set out to verify those of which he had been advised, but because of his age and limited resources, could only do a valiant, rather than complete, job. He sent information about several unverified locations, including several John Paulding Doughboys, with descriptions indicating they were Viquesney Doughboys, in a response to a Smithsonian project. The result is that confusion has increased because of their inclusion in the Smithsonian’s Inventory of American Sculpture (IAS). Smithsonian representatives are aware of this and have indicated their willingness to make any corrections for which documentation is received, but once a report by Mr. Wesley was turned in, proving to the Smithsonian that a statue was incorrectly identified or never existed has been frustrating, such was his reputation as a Viquesney researcher.

After I had seen a few Doughboys and knew the locations of a few more, I wanted to see if I could find out where the others were, how many there were, and other information about them; I didn’t imagine there would be anywhere near as many as there are. In going through the Henryetta, Oklahoma library files during a visit there, I encountered a copy of T. P. Wesley’s letter to Home and Away, but the copy I saw didn’t indicate the name of the magazine or its date, so I couldn’t contact them. It did, however, have Mr. Wesley’s home address at the time. So I went through information operators. When I told the information operator his name, her response gave me the distinct impression that she knew of him. Fortunately, he still lived at that address and I managed to reach him on the phone. His hearing was very bad and after an attempt to introduce myself and the reason for the call, he told me that he was 92 and I’d have to speak up and speak slowly and clearly, so I started over. At the word, “Doughboy,” he took over. The dear man talked for about 45 minutes without pausing. I heard more about Doughboys than I thought possibly existed. I learned the rough number that exists. I heard of a stone one in my wife’s hometown that she hadn’t recognized as being one because it is stone. He even told me a humorous old story about the one in Henryetta and the name of a clothier he knew there when he was selling men's clothes in Oklahoma City in the 1920s. I could hardly get into the conversation – but he probably wouldn’t have heard me anyway. Before the call ended, we exchanged addresses and phone numbers and agreed that we would be in contact.

Within a few days, I had a thick package of information he’d mailed me about Viquesney and the Doughboy, and about Spencer and Owen County, Indiana – he was very proud of both. As we continued to have contact, he’d have Mary Lee Brinson, who lived a few doors from him in the same senior citizen apartments, listen to me about things he didn’t hear clearly and repeat my comments or questions to him. Then he would get on the phone with his deep voice and my end of the conversation was over again – but it was always enjoyable. Mary Lee also helped in his mailings to me. Over time, I learned how dependent he was on Mary Lee’s help and how strong their feelings for one another were, and she became an integral part of the relationship.

So Mr. Wesley was my very good friend, as was Mary Lee. We communicated often, even visited Viquesney’s grave together and dined at his favorite eating place, Spencer’s Canyon Inn at McCormick Creek State Park. I visited the office that the Evening World still maintained for him forty years after he had sold the paper, and I got to meet all the people there that he loved so much. I still communicate frequently with Mary Lee.

Since Mr. Wesley’s vision and writing had started to fail, he made me some audio tapes to record his recollections of Viquesney and Doughboy facts, and other things about Spencer and Owen County. I’d send him empty tapes to record more.

In early 2000, I took my two sisters on a 11 day driving trip to renew childhood memories, and we spent some of that time in Spencer so we could all share time with Mr. Wesley and Mary Lee. We also managed to see six Doughboys on the trip - plus one John Paulding Doughboy and three dead ends with no doughboys. Actually, we had a fourth dead end when we couldn’t get inside the Evansville American Legion Post to see their Doughboy.

Mr. Wesley moved to a nursing home – Owen Valley Health Campus – in September 2000 and spent his last nine months there. I was able to talk with him just a few times after the move, but Mary Lee and I were in very frequent contact and she would tell him of my calls. During his last months, I helped him by responding to two reporters writing articles about war monuments and his 50-year search for Doughboys, and to Don Conrad, who was compiling a travel guide to WWI monuments. Tom Douglas, editor of the Spencer Evening World, (now retired) also helped him.

Mr. Wesley died at Owen Valley early on June 4, 2001, just 25 days before his 96th birthday and I made calls that day to try to tell some of his “Doughboy Searchers” he had told me about. He is especially missed by his daughter, Betty Jo Blunk, by his dear caregiver and special love of his last few years, Mary Lee Brinson, by Tom Douglas and the entire staff of the Evening World, by many Spencer residents (he was called “Our Mr. Wesley” in Spencer), by his “Doughboy Searchers,” of which there have been quite a few – and by me. So highly regarded was the man, that in his memory there is now a T. Perry Wesley Community Leader Award presented annually to deserving Owen County residents by the local Chamber of Commerce.

One of the reporters I helped for Mr. Wesley was Reuters reporter Phil Barbara who was writing an article about Mr. Wesley’s 50 year quest to locate Viquesney Doughboys. Robert Widener of VFW Magazine contacted me about the same time about an article they were publishing in their Memorial Day issue, and it was as a result of contacts with one of the editors of the magazine that Les Kopel first learned of me. Mr. Barbara’s article was originally planned to be a Memorial Day article, but he became concerned that Mr. Wesley might not live that long, so it was published May 17, 2001. Mr. Barbara had been able to talk with Mr. Wesley on a limited basis and quoted him to me as saying that when he was gone, a man in Texas named Earl Goldsmith would pick up his search. Mr. Barbara was going to Europe later in May, I think to do an article about D-Day. He was concerned that Mr. Wesley would die before he returned, so he wrote an obituary and gave it to the person at Reuters in Washington D. C. who was in charge of releasing things at the correct time (City Desk, City Editor, or something like that). He then called me and gave me the phone number to call to reach that person as soon as I learned Mr. Wesley had died. I called the number on June 4 and they released the obituary. Unfortunately, it wasn’t picked up by a lot of newspapers because of the lack of widespread interest. I found it on the Internet at the time, but for the life of me, can’t locate a copy in my files.

Back to Mr. Wesley’s statement that a man in Texas would pick up his search: I didn’t have any plans along those lines, even though I was interested in seeing a few. By the time Mr. Wesley died, I had probably seen about fifteen. I had the Smithsonian list and was already aware of some corrections that should be made to it. I had an immense appreciation for Mr. Wesley and enjoyed knowing about Doughboys, but I wasn’t bent on trying to pinpoint all of them or come up with an authoritatively correct list of locations.

Within days of Mr. Wesley’s death, that changed. I just decided that I would start spending time trying to run down all the information I could about them. Since then, I’ve had phone conversations and written communications with people all across the country. I hacked along and made quite a bit of progress by myself for a while, and then Les Kopel came along to give me a big and continuous boost.

Mr. Wesley’s records contained about 35 erroneous Viquesney Doughboys, but did not reflect about 35-40 other genuine ones that have since been located. In the end, he had settled on a number that is very close to the number that is actually known. Les and I have combined efforts to compile a list that contains only Viquesney's World War I Doughboys or copies by other artists but credited to him, or not credited but using his original molds.

As time passes, we will find more.